WATCH

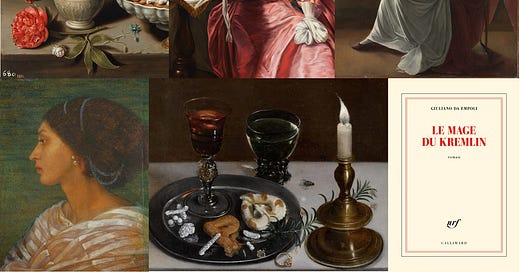

Recently read The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel; these were some of the stand-out pieces I loved, and hadn’t encountered before, mixed in with some new favourites found elsewhere.

Joanna Bryce Wells, Study of Fanny Eaton, 1861

Marie Denise Villers, Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d'Ognes, 1801

Marie Laurencin, Les Jeunes Filles, 1910-11

Rachel Ruysch, Still Life with Flowers on a Marble Tabletop, 1716

Rachel Ruysch, Vase of Flowers with an Ear of Corn, 1742

Marie Laurencin, Trois Jeunes Femmes, 1953

Rosalba Carriera, A Young Lady with a Parrot

Rosalba Carriera, L’été

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Untitled (after Joseph Wright), 2020

Eva Juszkiewicz, Untitled (after Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun), 2020

Clara Peeters, Still Life with Nuts, Candy, and Flowers, 1611

Clara Peeters, Still Life with Dainties, Rosemary, Wine, Jewels and a Burning Candle, 1607

READ: The Wizard of the Kremlin by Giuliano da Empoli (trans. Willard Wood)

I didn’t expect this novel to be as good as it was, honestly. It’s a fictionalized account of a political advisor within the Kremlin, alongside Putin’s rise to power (probably loosely modelled on Vladislav Surkov), spanning the chaos of the nineties in Russia, post-collapse, to present day. The translation is incredible, and while, sure, there are a few uneven moments, I had trouble putting it down every time I picked it up.

“Russia is the West’s nightmare machine. At the end of the nineteenth century, your intellectuals dreamed of revolution. We had one. You never did more than talk about Communism. We experienced it for seventy years. Then came the era of capitalism. And even there, we went further than you. In the 1990s no one deregulated, privatized, or gave more scope to entrepreneurial initiative than we.”

Re: that specific moment in your late twenties: “I felt exhausted yet I still hadn’t done anything.”

“In the early 1990s, Moscow was an electric city. We’d just turned twenty, and a new world was opening up before us, right when we were finally strong enough to conquer it. The streets of Moscow, the giant Stalinist buildings, the muddy sidewalks, and the big ceiling lights in the Metro were all still the same, but everything suddenly seemed to exist within a bubble of energy.”

“That’s how power works in Moscow, it has never been divided from life. In your country, the men who hold power are just accountants. Gray figures who wake early in the morning, eat whole-grain muesli, and shut themselves in an office for ten, twelve, or fourteen hours to do what they have to do. Then they climb into their cars and ask to be driven home, or dropped off at a dinner party with other bores, or, at best, taken to see their mistress. End of story. In Russia, that would be inconceivable—we have a holistic conception of power.”

“In the early 1990s, Gorbachev and Yeltsin led a revolution, but most Russians woke up the next day to a world that was unfamiliar, one they didn’t know how to navigate. Before the American and the European dreams collapsed, there was the collapse of the Soviet dream. No one in your part of the world noticed, because it didn’t seem possible that anyone could build a dream from such poor, colorless things: a respectable profession as a bureaucrat or a teacher, a compact Zhiguli, a dacha with a kitchen garden, vacations in Sochi and occasionally in Varna, where you could wade the Black Sea and look forward to a good barbecue with friends. Yet this model had a power and a dignity all its own. Its heroes were the soldier and the schoolmistress, the long-haul trucker and the blue-collar worker—it was they who populated the billboards plastering the streets and subway stations. The new heroes, the financiers and supermodels, took over, and the guiding principles of the USSR were overthrown. They had grown in up a nation and now found themselves in a supermarket.”

“You self-righteous Westerners think that anger can be absorbed, that all it takes is economic growth and technological progress, along with affordable home delivery and mass tourism, to dissipate the people’s wrath, the silent, sacrosanct anger of the people… It isn’t true. There will always be people who are disappointed, who are frustrated, who are on the losing end in every epoch and under every government.”

“No one should feel too sorry for the Russians. They have one hundred and twenty television channels.” “But those channels all tell the same story, Vadya, like in Brezhnev’s time.”

“‘Caligula wished that all men had but one neck, that he might reduce the whole world to nothing with a single blow.’ Power in its pure state. That’s what the tsar had become. Or maybe he was that way from the start. The only throne that will bring him peace is death.”

“You’re asking too direct a question, he said. Power is like the sun, like death: you can’t look at it head-on. Especially in Russia.”

It was also absurdly hilarious at times: “He [Cardinal Richelieu] passed a law that forbade two adult males from challenging each other to a sword fight, can you imagine? Western man has never recovered. From there to paid paternity leave was just a small step.”

LISTEN: Puma Blue, A Late Night Special

Until next time,