Some art I love, some art I’m not entirely sure about but keep going back to, trying to figure it out for myself. Poetry by Arseny Tarkovsky, and thoughts on translation from his translators. A beautiful piece of music.

WATCH:

Tamara de Lempicka, Woman with Arms Crossed, 1939

Manoucher Yektai, Blue Table, 1960

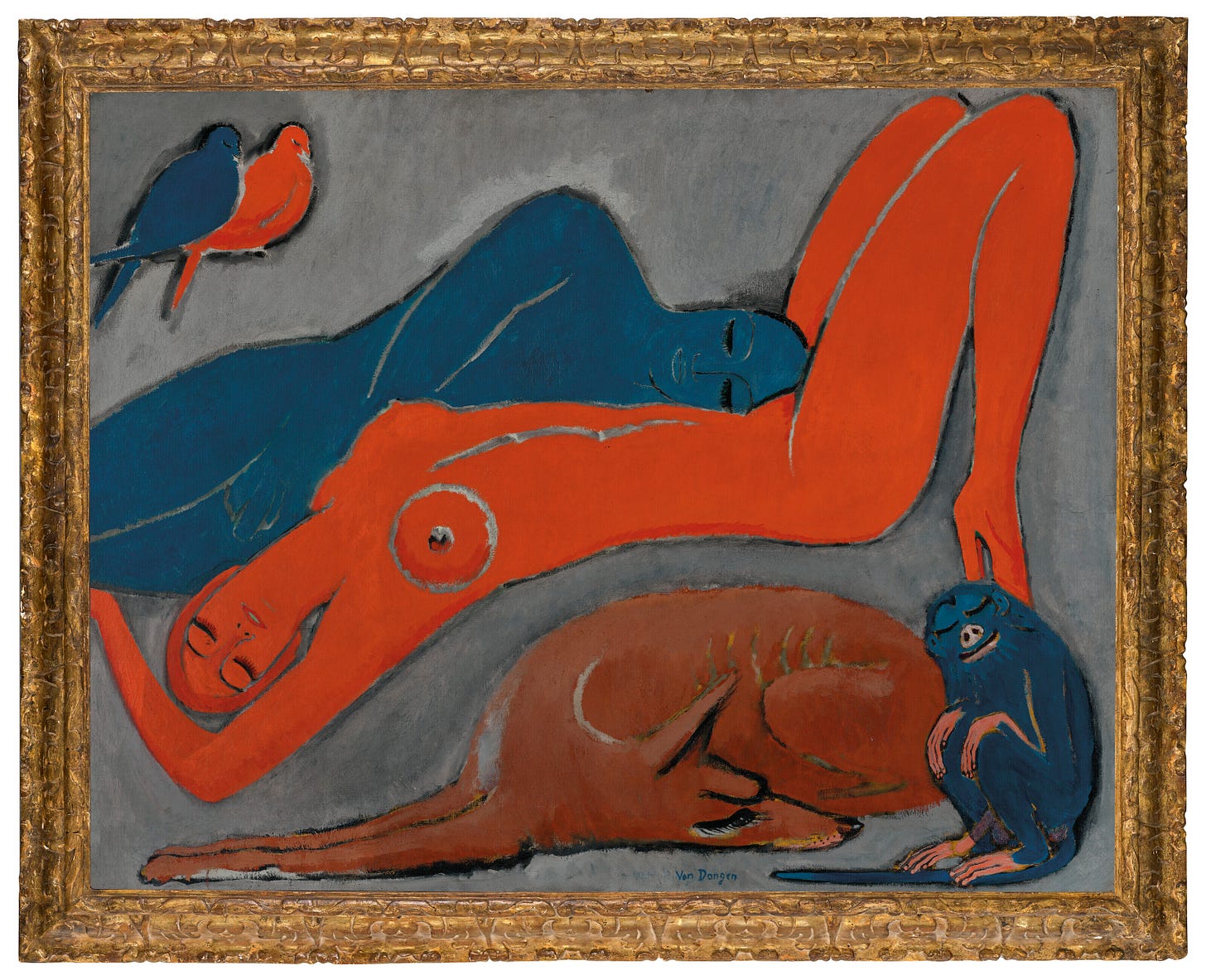

Kees van Dongen, La Quietude, 1918

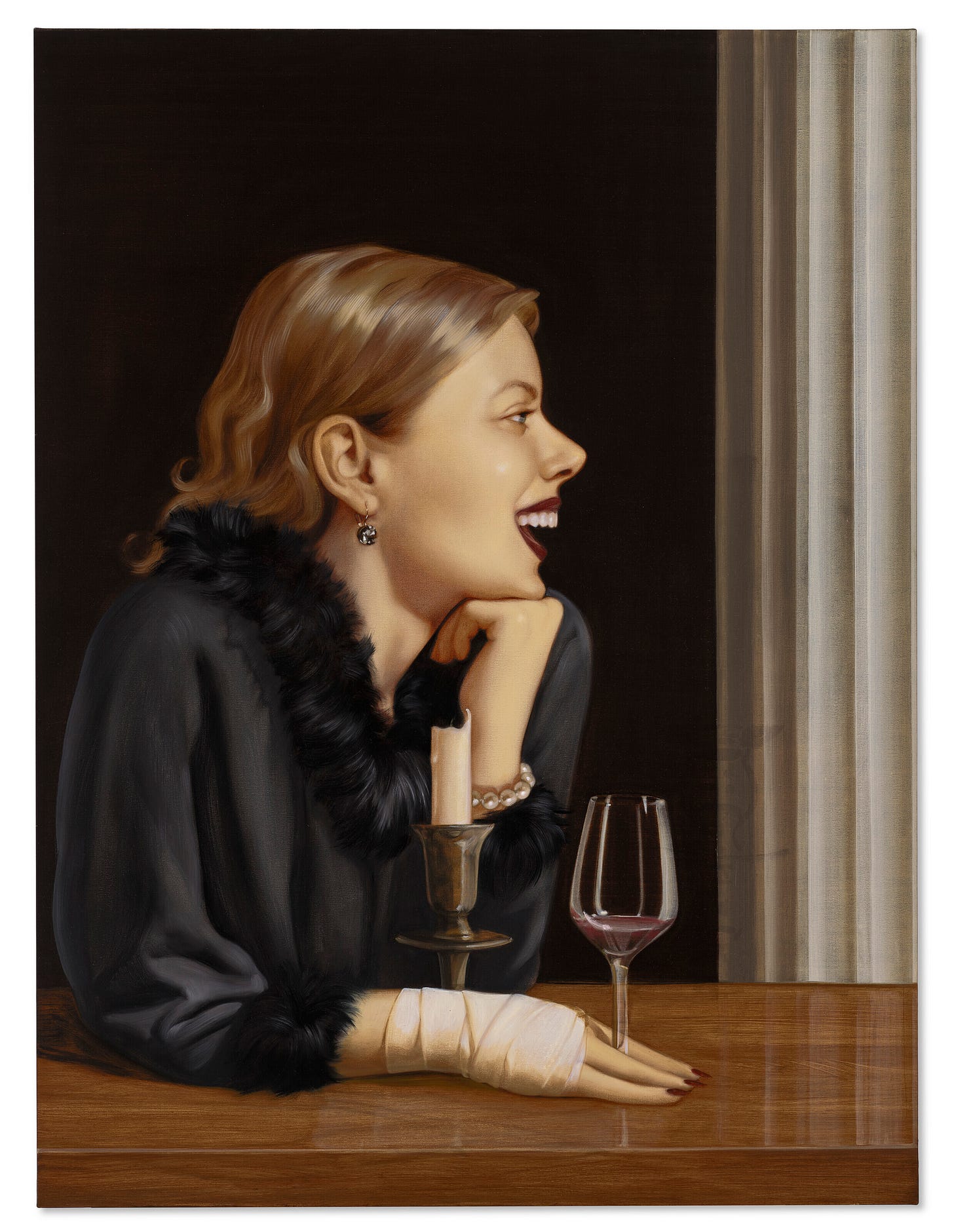

Anna Weyant, Loose Screw, 2020

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Blue Whale a.k.a. #12, 1983

This is one of the pieces I do actually love. I went into the new Whitney Biennial expecting to be underwhelmed, and instead was really taken by some of the art.

Jacob van Hulsdonck, Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Pomegranate, 1620

Anna Weyant, Head, 2020

Manoucher Yektai, Tomato Plant, 1959

Like with O’Neal, Yektai’s paintings are new favourites for me.

Tom Rosenthal album cover, Denis was a bird

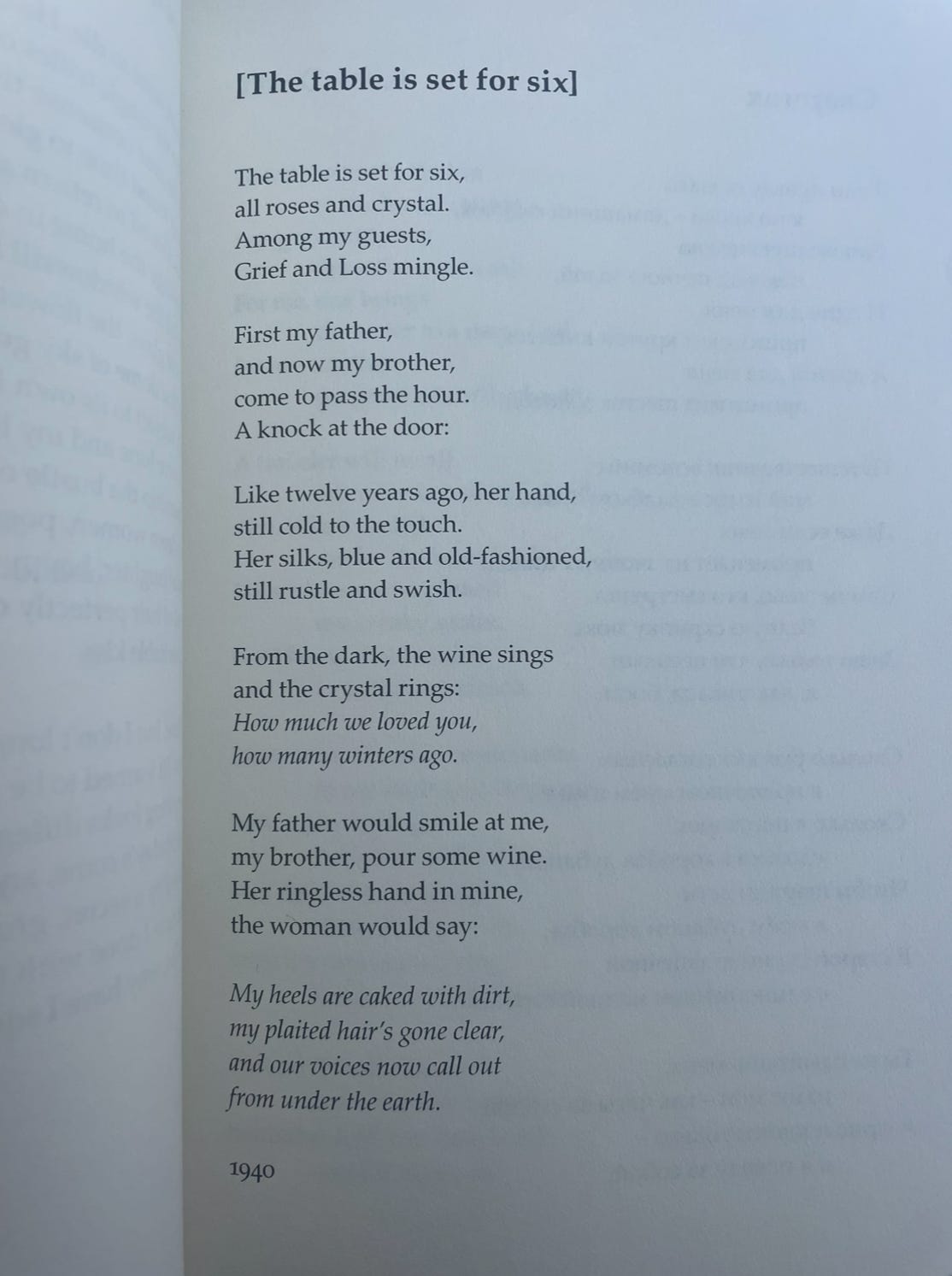

READ: Arseny Tarkovsky, I Burned at the Feast: Selected Poems

Many people—including your local film bros—love to talk about Andrei Tarkovsky, the Russian film director famous for Stalker, Solaris, and Nostalghia.

The above still is from Tarkovsky’s loosely autobiographical Mirror. It excerpts the concluding lines of “First Meetings,” a poem by his father, Arseny Tarkovsky, one of the foremost 20th century Russian poets. It’s also translated often as “First Dates,” or “First Times Together.” Throughout the film, Tarkovsky weaves in his father’s poems. In particular, the sequence in which “First Meetings” is read (starting at about 0:55 in the below clip) is haunting and beautiful, somehow heartbreaking. It led me to pick up a collection of his poetry, I Burned at the Feast: Selected Poems of Arseny Tarkovsky (tras. Philip Metres and Dimitri Psurtsev), which I’d recommend.

In addition to “First Meetings,” some of my other favourite Tarkovsky poems are “Passing By,” “I Bid Farewell to Everything I Was,” “From Chistopol Notebooks: VIII,” and “[The table is set for six],” with their lines such as:

“If God could not save you from the grave, how could I? How could I fall in love? Wake up. Come back. I’m dying of grief.”

“…while behind us, fate followed/like a madman with a razor in his hand.”

The collection’s afterword — “Erotic Soyuz: 25 Propositions on Translating (Arseny Tarkovsky)” by Philip Metres — also had some of the most beautiful thoughts on language and translating I’ve read:

“It turns out that failure—the dominant metaphor in so much talk about translation—is not the right metaphor at all. How’s this? Translation as erotic/asymptotic—about nearing, longing, stretching one’s language toward what it might become. The original as sacred text toward which we long. If poetry is, as Allen Grossman has proposed, an Orphic attempt to reach the Beloved, then the translator is nothing if not Orpheus, at every moment longing to turn and be sure that the beloved still follows. Only a complete turn back will cause the beloved to fade forever. I’m reminded, suddenly, of the moment I learned that in polite written Russian, the addressed ‘you’ is always capitalized, and the word ‘I’ is not.”

“Yet, the translator believes that different languages have enough open edges, even contact zones, like the human body, that they can near or even touch each other. The closer the worlds of those languages (for example, Romance languages or Slavic languages or Finno-Ugric languages), the most edges will fit (almost seamlessly, with other edges.”

“Language dictionaries suggest otherwise, but the very fact that words have deep roots makes exact one-to-one word translation difficult, one step more difficult than seeking synonyms in Roget’s Thesaurus. If you’ve done this before, you know exactly what I’m talking about. Have a word, then try to find an adequate synonym. Each possibility feels slightly off, like glasses with the wrong prescription. And each synonym for synonym leads you further and further from anything that approximates seeing. Every word, every word worth its salt, carries with it a kind of irreducible particularity—its primal sounds, its weight in the mouth, its richly layered conscious and unconscious connotations and associations, both public and private. Words are like people, only older and more idiosyncratic.”

“Even if the Russian literary tradition does delve deep into the darkness and misery and mystery of human existence, the music of Russian poetry is so undeniable, so playful, so often ecstatic, and has persisted for so long, it suggests the secret pleasures of a people who have been seen in the West as the stern patrons of unhappiness (“every unhappy family,” etc.). It is, indeed, what makes translating Russian poetry most difficult, and why readers of Russian poetry in translation—say, the English poetry version of Anna Akhmatova or Osip Mandelstam—mainly receive a picture of a grim and absurd reality but not much of a sense of what it sounds like when a pure music collides with the grim and the absurd.”

LISTEN: Peter Gregson, “II. Warmth,” Quarters: One- Four

Until next time,